The Easter season has come and gone, and despite numerous promises - mostly to myself - I still haven't completed this 'going through the motions' blogpost that I started months ago. I had started to think about putting completion off, er, completely until the LPAT ruled on the motions - but that hasn't happened either. Unlike Caiaphas and Ananias' experience in my Easter-favorite film, nothing has been decided. And I'm still sitting on the fence.

Maybe that will change. Maybe I've found my mojo tonight to finish this damn post. I said back in March, in Part 8 of this series ("The Kingsway Cases at the LPAT: An (Unrepresented) Party's Observations, Part 8: Derailed!"), that I'd get my act together - so here's hoping I have. But like so many in the community, I've really grown tired of all of this. But I can't give up - I'm 9 parts into this series now, likely with another 9 to go before it's all over. There are more twists and turns with this LPAT appeal than you could find in a pretzel factory.

Recap

To recap: the Case Management Conference for this matter was held in Greater Sudbury on November 6, 2018, in front of a 3-member Local Planning Appeal Tribunal (LPAT). The Tribunal "stopped the clock" for this matter after the CMC, due in part to the Toronto Rail Deck divisional court reference, which all parties acknowledged would have an impact on our hearing. The Rail Deck matter was finally heard by the courts just last week (April 24), but a decision has been reserved. When that decision issues, and if there are no appeals to it, it's very likely that the LPAT will move forward to schedule a second Case Management Conference at which it will provide the parties with a level of certainty around processes related to cross examining witnesses and entering new evidence.

But our own little hearing generated a number of questions related to processes, too - and the parties who raised these issues believe that the LPAT itself has the ability to decide on the issues via motion submissions. At this time, no party has indicated that it will pursue process matters at divisional court - but it remains possible that a Party might yet do so, or the LPAT itself may refer matters to divisional court, similar to what it did with Rail Deck.

Let's go through the motions now, to see what, exactly, the parties want the LPAT to rule on. I'll offer my own thoughts along the way, for what they're worth (and honestly, they're likely not worth very much - without knowing whether the divisional court in Rail Deck is going to rule on whether the LPAT should be more like a decision review board or more like the OMB, it's hard to anticipate where a lot of this stuff is going to land).

LPAT Orders Certain Motions to be Filed

Motions were filed by legal counsel for Tom Fortin, Christopher Duncanson-Hales, and the Downtown Sudbury Business Improvement Area (whom I'll refer to from now on as the "primary appellants" - all of whom share legal counsel in Gordon Petch); the City of Greater Sudbury (represented by legal counsel Stephen Watt); and "the added parties" - 1916596 Ontario Limited - who is the applicant, aka the landowners, which include Sudbury developer and Sudbury Wolves hockey team owner Dario Zulich (represented by legal counsel Daniel Artenosi) and Gateway Casinos (legal counsel Andrew Jeanrie) filed a joint motion. The two unrepresented parties - myself and John Lindsay of the Minnow Lake Restoration Group - did not file any motions. Because we are so clearly in way over our heads here.

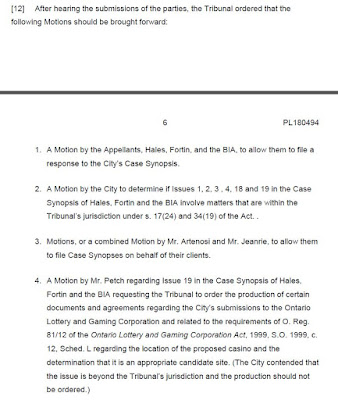

Here are the Motions the LPAT ordered the parties to make, after hearing their submission at the CMC:

|

| Motions Ordered by the LPAT |

Let's look at the motion made by the added parties first, as it's probably the most straightforward - and there may be a little something to write about with regards to an anticipated outcome, thanks in part to a recent LPAT decision on a matter in the City of Kawartha Lakes.

The Added Parties

As indicated earlier somewhere in this blogseries, the landowner/applicant to a planning matter is no longer considered automatically as a Party to the proceeding at the LPAT. Only a municipality/approval authority and the appellants are automatically given Party status. An applicant - who is usually a property owner who filed an application with a municipality, paid a fee, likely paid for most of the technical studies to support the land use change request, and who clearly has a fiscal interest in the outcome of any proceeding at the LPAT - well, they've got to now approach the LPAT on bended knee and request Party status.

Based on my read of a number of LPAT decisions, it's become quite clear that these sorts of requests for Party status have already become routine no-brainers for the Tribunal: the land owner has an interest in the outcome and needs to be front and centre at a hearing - especially if a mediated solution is going to be sought. But not just then. Although the LPAT can't vary a municipal decision after the outcome of the first round of hearing an appeal to an Official Plan amendment or a zoning amendment, it can make recommendations to a municipal Council when it boots it back to them for reconsideration. Those recommendations ought to be informed ones - and the landowner needs to be present in all of these situations.

In our hearing, all parties consented to the addition of the applicant/landowner, and to the addition of Gateway Casinos - who has a fiscal interest in the outcome - to be added as parties. The LPAT added both parties to the matter at the November, 2018 CMC. But these new parties, having only just been added by the LPAT, did not have a chance to respond to the Case Synopses filed by the appellants in the same way that the City of Greater Sudbury did. In effect, the legislation and the Rules of the LPAT allow the two new parties to participate - but don't permit them an opportunity to file any materials.

Now, that might seem just fine if the LPAT is going to act truly as a body that reviews municipal land use decisions. Think about it. The idea here is that all of the evidence germane to the appeal would already have been filed at this point - with the municipality that made a decision. If the applicant had a planner (and he did) that planner would have filed a planning report with the City (which he did) and the City would have forwarded that material along to the Tribunal and appellants via the enhanced municipal record (which the City did). So the basis for the applicant's case should already be on file, and available for their reference, right?

|

| Motion - Added Parties - Purpose of Motion |

Well, the added parties don't see it that way. Via motion, Zulich and Gateway are asking the LPAT to grant them leave to individually file their own case synopses and appeal records, which could include affidavit evidence. The LPAT's Rules seem to suggest that "appeal records and case synopses" are intended to only be filed by appellants (see Rule 26.11). The added parties acknowledge in their motion that there is no specific Rule of that specifically provides an added party with an opportunity to introduce an appeal record/case synopses, but the LPAT has the ability to do so based on their interpretation of Rule 26.20 - which allows the LPAT to add parties " on such terms as the Tribunal may determine." Further, the added parties submit that doing so is necessary as a matter of natural justice.

In response, counsel for the primary appellants asserts that since the added parties did not express to the Tribunal that they would be seeking additional rights once added, that the primary appellants would not have assented to the inclusion of the added parties as parties without debate/discussion of these rights. As a result, the primary parties assert that the added parties motion should fail.

The added parties assert that the Tribunal, as per a rather flexible read of its Rules, has the ability to require the production of a case synopsis/appeal record. I have to admit, at the CMC, I raised this matter with the Tribunal, because as an appellant, it looked to me that if the added parties were allowed to do this, I would need to file further responses. Clearly, I don't think it is necessary for the added parties to file these materials - but I'm not privy to how they want to make their case. Anyway, at the CMC, counsel for one of the added parties shut me down - said the authority is there, in the Rules - and I think he's right. It's not spelled out explicitly, but the Tribunal clearly has a wide range of latitude regarding what it can do when authorizing a new Party.

The question is, should it? The added parties here rely primarily on natural justice - and that may be enough. The primary appellants response that the added parties are seeking a new "right" just doesn't seem to hold up - the "right" is there in Rule 26.20. And I feel a lot more comfortable writing all of this - which is in complete contradiction to the legal counsel of the primary appellants - after having read the LPAT's April 18, 2019 decision regarding Case PL180734 in the City of Kawartha Lakes.

Kawartha Lakes and Added Parties

|

| From LPAT Decision - re: Added Party / Case Synopsis |

In the Kawartha Lakes matter, the City didn't bother showing up at the hearing. But the applicant did, after having appropriately petitioned the Tribunal to be added as a Party. Once added, they requested the Tribunal to allow them to file a case synopsis and affidavit material on the grounds that since no one else was going to do that, they had no choice but to. The LPAT agreed - and ordered that, in this scenario, it would be appropriate for the applicant to essentially act as a substitute for the no-show municipality. That's an interesting case on its own, but the take-away for the Sudbury matter is that the LPAT authorized all of this as per its interpretation of the LPAT Act and the Rules. So clearly the LPAT believes it has the authority to be able to Order an added party to file a case synopses and corresponding affidavit evidence.

|

| From LPAT Decision - Authority to determine appropriate actions for added parties |

The only question now is whether it's appropriate to do so in the Sudbury matters. And there might be something in the LPAT's Kawartha Lakes decision about this, too.

|

| From LPAT Decision - Tests for a 'balanced and leveled presentation of the argument' by both sides |

In [58], the LPAT identifies that the resolution of the hearing must be "fair, just and expeditious" based on a "leveled presentation of the argument and submissions of both sides in the appeal." To achieve this outcome, the LPAT appears now to have established two tests.

The first test, found in [59] is the requirement for a thorough response to the appellant's case synopsis. In Kawartha Lakes, the LPAT didn't have that, because the City didn't want to get involved and did not respond to the appellant's case synopsis. That's not what happened in Greater Sudbury, though - the City did respond to the appellants. So strike one for Zulich and Gateway here.

The second test, found in [60], suggests that the Tribunal has to have all relevant evidence and pertinent materials in front of it to support the response. It's not clear whether that happened in Kawartha Lakes (because the City didn't show up to confirm its due diligence in filing materials, and the LPAT could not question it), but it is pretty clear that in the case of Greater Sudbury, everything that's needed to support a thorough response to the appellant's case synopses has been filed - because the City has already relied on it for its response. Strike two for Zulich and Gateway.

And since there are only "two sides" here - it's incredibly unclear whether Zulich and Gateway have anything meaningful to add to the "argument and submissions" that hasn't already been made.

But what about natural justice? That's something that the LPAT is going to have to wrestle with - and frankly it's part of the bigger picture about what, exactly, the LPAT wants to be / should be. Are we talking about keeping the LPAT as a very limited review body - available only to decide on narrow grounds whether a municipal decision on zoning or official plan amendments appropriately considered provincial and municipal policy? Or is the LPAT really intended to be something bigger, more akin to the OMB - but without the 'hearing do novo' starting point? The added parties seem to want it to be the latter, but it seems to me that the LPAT believes it really ought to be the former.

And that seems to be illustrated in what I think is Strike Three for the added parties here. It seems that the LPAT, out of an abundance of caution that this Kawartha Lakes ruling might be used by added parties to further expand the level of their participation, in the same decision at [62], the Tribunal makes it darn clear that this isn't going to happen in all circumstances - particularly where the LPAT feels that it has enough to move forward.

|

| LPAT Decision - Clarification |

And that's why I think the added parties are going to be out of luck on this motion. The LPAT already has the City's response to the appellants' case synopses. It does not need anything further from the added parties to come to a "fair, just and expeditious" resolution.

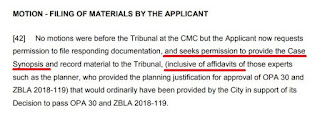

New Evidence

Just one last thing about this. Note that at the CMC, the LPAT ordered the added parties to individually or together file a motion to allow them to file a case synopsis. But the added parties actually filed a motion for three things: 1) file a case synopsis; 2) file appeal records; and, 3) affidavit evidence. Note that the last two matters appear to be out-of-scope with the LPAT ordered - and counsel for the primary appellants certainly brought that to the attention of the LPAT.

While I might not know for sure what "appeal records" are, I can't help but think that they would be documentation pertaining to the case synopses. As an appellant, I can't help but wonder whether the intention here is to file new evidence - something that I thought the legislation (LPAT Act) and Rules prohibited. As an appellant, it has not been my expectation that I would ever need to "respond" to someone else's case - the only 'response' that the legislation and rules appear to permit is the City's response to my case (and the cases of the other appellants).

The added parties maintain these materials are needed in order to make their case. All the more reason - if the LPAT really is to be a municipal decision review panel - to reject the motion of the added parties. And all the more reason the motion will be rejected.

Motion of the City - Jurisdiction

So ya, that was the easy one. Let's now turn to the motion filed by the City of Greater Sudbury with regards to the case synopsis of the primary appellants. The City, via motion ordered by the Tribunal, submits that the Tribunal should Order the deletion of certain issues raised by the primary appellant.

|

| CGS - Motion Purpose |

The basis for the City's position on all of these issues is informed by the legislation, and specifically the requirements for appeals under 17(24) and 34(19) of the Planning Act to only be made on the basis of inconsistency with the provincial policy statement; failure to conform with or does conflict with a provincial plan; and, failure of conformity with an official plan. The City asserts that issues 1, 2, 3, 4, 18 and 19 do not meet these statutory requirements and therefore should not be heard.

Issues 1, 2, 3, 4 and 19 - Willing Host

The primary appellants assert that the City of Greater Sudbury has never undertaken its due diligence to meet the regulatory requirements of O.Reg. 81/12 of the Ontario Lottery and Gaming Act. This assertion forms a significant element of the primary appellant's arguments related to the matters before the LPAT regarding the casino (for more on that case, see: "The Kingsway Cases at the LPAT: An (Unrepresented) Party's Observations, Part 4: The Strong Case Against a Casino"). Taken together, this is where the primary appellants assert that the City has never undertaken an appropriate evaluation with public participation around whether the City is a 'willing host' for a full casino gaming facility. And Issue 19 requests production of documents from the City regarding how it arrived at the conclusion the City would be a 'willing host' in absence of a O.Reg. 81/12 process.

The City believes that this really has nothing to do with the matter in front of the LPAT - and that if the primary appellants want to pursue this, the right venue would be something other than the LPAT, given its limited jurisdiction.

After reviewing O.Reg. 81/12, and having earlier participated in the only opportunity for public feedback related to a casino in the City of Greater Sudbury (an information session held at City Hall in the early fall of 2012 - one where the public was asked to comment on four sites - none of which included the present proposed site for a casino; and the public was never asked whether it wanted to host a casino), it's clear to me that the City did not follow the process for determining 'willing host' as outlined in the Regulation. Despite this, however, it's also clear that the OLG doesn't agree with my interpretation (or that of the primary appellants) of the Regulation in this instance, as the OLG has already greenlighted a full casino gaming facility in Greater Sudbury. The OLG based its decision on a submission made by the City - a submission that the City now cannot or will not reproduce for this hearing.

But none of that may matter. If the LPAT determines it has no jurisdiction to delve into whether the City and OLG adhered to the regulatory requirements for 'willing host', these issues will be dead in the water.

But here's why this is important. It's the way in which the City has moved that the LPAT lacks jurisdiction. If the City's interpretation is favoured by the LPAT, then the LPAT will be binding its hands for all time with regard to what, exactly, it can base its own decisions on. The City argues that the LPAT is constrained by the limited scope of the Planning Act - at least as it applies to appeals related to official plan and zoning amendments.

|

| Primary Appellants response to CGS Motion re: Jurisdiction |

The primary appellants can't buy that - and are relying on the LPAT Act for a broader interpretation of the scope of the LPAT's authority. Section 11(2) of the LPAT Act indicates that "The Tribunal has authority to hear and determine all questions of law or of fact with respect to all matters within its jurisdiction, unless limited by this Act or any other general or special Act." That's a little different from the old OMB Act, quoted by the primary appellants above. The City argues that questions of law and fact are, in this case, limited by the 17(24.0.1) and 34(19.0.1) of the Planning Act.

And ultimately, I think the LPAT is going to agree with the City for precisely that reason - the new provisions of the legislation, which seek to make the LPAT a decision-review panel for these types of matters, don't authorize the LPAT to delve into the question of whether a land use is actual legal within the municipality. While I know the City failed to live up to legislative requirements on 'willing host' - it appears to me that the LPAT can't go there. And based on decisions like Kawartha Lakes, where the LPAT appears to be going out of its way to limit its jurisdiction, I expect the LPAT to exclude the primary appellants 'willing host' arguments.

With one caveat: if the Divisional Court rules in the Toronto Rail Deck matter so as to expand the powers of the LPAT instead of limiting them (rules against the City of Toronto and supporting municipalities), all bets are off. Of course, it is quite possible that the LPAT will rule on this motion before Rail Deck is resolved. But I suspect these matters related to jurisdiction are at least part of the reason the LPAT has been silent on the motions so far.

Issue 18 - Bias and Fettering

And it's this issue raised by the primary appellants, moreso than the 'willing host' matter that may have LPAT scratching its head. Issue 18 pertains to the assertion of the primary appellants that the decision made by the City of Greater Sudbury in April, 2018, and subsequently appealed by the primary appellants, was made on the basis of bias and in fact Council of the City of Greater Sudbury made the decision with its discretion fettered - which besides providing an unusual and perhaps unnecessary mental image, is contrary to law. The primary appellants assert that since this happened, the decision itself must be rendered a nullity, which I imagine is lawyer speak for "tossed into the trash".

Again, the City says that the LPAT lacks jurisdiction.

But here things are less clear. Unlike the 'willing host' matter, which was somewhat exploratory on the part of the primary appellants, the matter of fettering isn't - it's absolutely a question of law. And here the primary appellants argue that the LPAT, via Section 11(2) of the LPAT Act, has the ability to determine questions of law through something called 'shared jurisdiction'. Petch points out that the old OMB used to do so routinely - and as examples notes how the OMB determined compliance with other legislation and instruments, such as the Environmental Assessment Act, Conservation Authorities Act, Municipal Act, Aggregate Resources Act, etc. Not only did the OMB rule on these matters, but it went through every effort to ensure that its own decisions complied with them - as required by law.

The LPAT is no different, argue the primary appellants. And limiting its jurisdiction to PPS consistency, and provincial and official plan conformity would be a complete failure and not in keeping with the need for the LPAT's decisions to comply with other legislation. Although I don't think the primary appellants say it this way, think of this example: what if a municipality makes a land use decision that isn't in keeping with, say, the Municipal Act, perhaps because the amendment being sought includes policy that directs the applicant to undertake an action not in keeping with that legislation. And what if the LPAT rules the same way, even after applying the consistency/conformity tests? If that's all the LPAT can rule on - as says the City of Greater Sudbury - than the LPAT would find itself in a situation of endorsing a municipal decision that would be against the law.

Sorry, but that's just inconceivable. And the LPAT has to rule the same way here - matters of law, because of shared jurisdiction, are in keeping with its mandate. The primary appellants actually point to the Rail Deck decision of LPAT that led to the stated case to Divisional Court as guidance here, indicating that the LPAT has already ruled on whether it can take on matters of law as part of its jurisdiction (and answered that question in the affirmative in the Rail Deck decision - albeit while referring the 'difficult' decisions in that matter to the Courts).

The problem with ruling in favour of the primary appellants on this motion is that the LPAT is now becoming something other than a simple municipal decision review panel. I fear, however, that there isn't any other choice - that horse is already out of the barn, thanks to Rail Deck

The LPAT can't tie its own hands here. The primary appellants make a persuasive case that this particular matter of law needs to be heard by the Tribunal, as it directly impacts the City's decision to approve the land use amendments in 2018. They've provided some serious case law around bias and fettering to support this assertion.

I'm flagging this one as having the potential to end up in front of the Courts - either by LPAT stating a case itself as it did in Rail Deck, or via the primary appellants. Their case here for bias and fettering is incredibly strong (remember all of those pre-public consultation comments from municipal councillors like Robert Kirwan - along with an agreement made between the City and the developer to acquire land at below-market value? Or the money the City spent on the Integrated Site Plan - before applications were ever filed? The appellants are sitting on a treasure trove of evidence that Council's decision was fettered - that they had a vested interest in making the land use decision they made. I think that anyone in the City of Greater Sudbury who has been following this matter would agree to that - and many would say, 'So what? The City wanted the KED and that's what it went out and got". But that's not how the land use planning process is supposed to work.

The Motions of the Primary Appellants

The primary appellants have made motions on two matters: 1) the production of certain documents, some of which are related to the 'Willing Host' matter described above; and, 2) that the LPAT give the primary appellants an opportunity to Reply to the City's Response to the appellants' case synopsis, in accordance with the laws of natural justice. Let's look at this one first.

Reply

The appellants provided their case synopsis, and the City responded to it. Now, the next step is to go to a hearing on that basis. The primary appellants contend that, under the OMB and in every other judicial and quasi-judicial venue, they would be afforded the opportunity to submit a reply to the City's response. The appellant's case here is hampered by the fact that the LPAT Act and the Rules don't specifically authorize or contemplate a Reply. But the primary appellants argue that the the LPAT has flexibility around this, in keeping with its Rules - and it should exercise that flexibility, in keeping with the laws of natural justice.

Although I, as an unrepresented Party, could care the less about the outcome of this matter, fact is it's a big deal. If the LPAT opens the door to Reply in this case, surely it will have little choice but to do the same for all matters before it. But since its own Rules are silent, and if it truly wants to remain a decision-review panel, than it may come to the conclusion that despite natural justice, there's no need for reply. And that could be a problem for the whole legal community.

No doubt the LPAT is examining this one very carefully. I'm going to flag this as having the potential for winding up in front of Divisional Court too, out of an abundance of caution. I expect to see a stated case to Divisional Court from the LPAT on this. The stakes are just too high to get this one wrong.

Regarding production, the primary appellants have asked the City to produce certain documents related to 'Willing Host'. If the LPAt finds in favour of the City on 'Willing Host' you can bet those documents will not be ordered produced. And the opposite is true if the LPAT favours the appellants on 'Willing Host'.

Production

The primary appellants have also requested that the City produce the Downtown Master Plan and "From the Ground Up 2015-25 - the City's Economic Development Plan. The appellants relied heavily on these strategic documents as part of the basis for their appeals (all of the appellants - me included). The City contends that these documents are completely irrelevant to matters before the LPAT, as they had not been incorporated into the official plan at the time municipal decisions were made). Apparently, a request had been made by counsel for the primary appellants for the City to provide economic development strategies with similar names, some of which are referenced in the 2006 Official Plan (but have been superceded by newer documents - example: the former economic development strategy was replaced in 2016). The City has not provided these older documents.

First, let me say this, as part of my appeal is based on the notion that the Downtown Master Plan and Economic Development Plan are related to the matters in front of the LPAT: the City's claim of irrelevance is specious at best, and the LPAT will have to decide at a hearing whether the City is right about this. I remain convinced the LPAT will decide against the City on this matter, due to a provision in the Growth Plan for Northern Ontario which requires approval authorities to consider these types of plans/strategies when making decisions.

But whether or not that's the case, I just can't understand the City's intransigence here of not providing these documents to the primary appellants. The City can't have it both ways. It can't say that it's new economic development strategy doesn't apply because there is no reference to it in the Official Plan - and at the same time insist that its old economic development strategy, which is referenced in the Official Plan, also does not apply because it's been superseded by the new strategy.

LPAT rules in favour of the primary appellants on this part of the production request.

One Last Motion to Go Through

And finally - the motion that no one has talked about, including the LPAT: legal counsel for Zulich filed a motion to the LPAT to have the appeal of the Minnow Lake Restoration Group filed by John Lindsay disposed of without holding a hearing on the grounds that it discloses no planning reasons.

The LPAT has ruled that this motion was submitted out of order. It was not one of the motions that the LAPT itself ordered - and therefore Zulich is going to have to wait.

But John is ready - and in my opinion, the motion against John is complete crap. I get that I'm not the high-priced lawyer who wrote and filed the motion (and really, what do I know?), but I have absolute confidence that the LPAT will not rule against John because a) he did disclose a number of land use planning questions in his appeal, and those questions were not based on apprehension as the lawyer for Zulich contends, but were rather based on provincial policy and the technical studies submitted by Zulich in support of the applications.

In my opinion (and it is just my opinion - I have no idea how John feels about this), there's a bigger game afoot here.

At the CMC, Artenosi, Zulich's lawyer, made it clear that he would be, at some point, asking the Tribunal to remove one Alexander Bowman from Expert Witnesses list. Bowman is Minnow Lake's technical expert - and the LPAT has specifically requested that he appear as a witness to speak to questions related to water quality. And this has to be very concerning to the City and the added parties - because he is the only technical expert presently on the Witness List who is going to speak to those issues.

How the hell did that happen? Did the City drop the ball on this?

First, let me say that with regards to Bowman's participation in the hearing, Artenosi might have a couple of really good points. The questionable point is, as Bowman himself did not provide any evidence to the City in advance of the municipal decision being made in April 2018, can he now appear as an expert for Minnow Lake because John included his evidence as an affidavit in his case synopsis?

The answer to that question - which would not have been apparent in November, 2018 - appears to be "yes". The LPAT appears to be routinely accepting expert witness evidence filed as affidavits to appellants case synopses - even though those experts did not provide oral or written evidence to a municipality before making a decision. The LPAT appears to be allowing this as long as said expert evidence doesn't veer into new areas for the appeal. So in Bowman's case, since John raised issues with water quality as per the Provincial Policy Statement, Bowman can talk about water quality.

My initial reaction to this was that all of this appears to be 'new evidence' and I think that's a part of the concern that was raised by Artenosi at the CMC. Bowman is likely to say things to the LPAT that no one ever really said to Council. Sounds 'new' to me - and yet....

And yet a very high profile case in Windsor, with a very high-profile "after the fact" expert, appears to be going forward without anyone blinking an eye. Windsor CAMPP appealed a municipal land use decision to permit a hospital on rural lands outside of the City's settlement area - something CAMPP argues isn't in keeping with the City's official plan. After making submissions to Council to this effect, CAMPP filed an appeal. After filing an appeal, it retained former Director of Planning for the City of Toronto (and former Mayoral candidate) Jennifer Keesmaat to provide affidavit evidence as part of its case synopsis. Like Bowman before her, LPAT has included her on the witness list. And I still worry that this opens the door to new evidence.

Bowman as Hinge

Anyway, even though Artenosi isn't likely to have Bowman excluded on that matter, based on materials filed in support of his motion to dismiss John's appeal, I think he's got an ace up his sleeve. For unlike Keesmaat, who is a professional planner, it's not clear that Bowman's qualifications will meet the LPAT's tests for an expert witness. No doubt Bowman's "expert" status will be challenged on those grounds - and on the grounds that Bowman has not behaved as an "expert" should - but instead has been acting as an advocate for the Minnow Lake position. And ultimately, even if the credential thing is decided in favour of Bowman, I just can't see the Tribunal treating him as an 'expert'.

Which means Bowman's evidence around water quality issues will be no better than my own. He, like me, will be just some guy offering up our own non-professional interpretation of how we think the PPS should work. And again, that's not exactly a winning strategy.

But without question, Bowman is a hinge in this hearing. The City and added parties need to exclude him - because if he is an expert, they've offered no one to rebut what he has to say. And to loop this back to the beginning where we discussed the motion of the added parties - that's probably why the added parties are seeking to have their own "appeal records" and "affidavit evidence" included now - because they don't want to risk having no one counter Bowman's expert evidence on water quality.

Frankly, I don't think they need to worry.

It's Miller Time

And now that I've gone through the motions, it's time for a nice glass of wine. Or maybe several shots of tequila. I hope you've had more fun reading this than I did writing it, but I think we're probably both worse off and in a bad place right now.

(opinions expressed in this blog are my own and should not be interpreted as being consistent with the views and/or policies of the Green Parties of Ontario and Canada)